The Milwaukee Journal, June 4, 1937

“Wright’s Upside-Down Column Tips Over Theories” “Holds Heavy Load in Test”

Industrial Commission Eyes New Method of Famed Wisconsin Architect at Building in Racine

Frank Lloyd Wright, Wisconsin’s internationally famous architect, Thursday won the first round of an encounter with the Wisconsin industrial commission. He successfully loaded 24 tons of sand on the top of a test column which he designed for the new administration building of the S. C. Johnson & Sons Wax Co., at Racine without cracking the pillar. The test was conducted on the site after the commission had questioned the structural value, of the column.

The district around the building site took on a holiday air as preparations went ahead to test Wright’s most recent contribution to architecture. Word of the trial had gone out to the building industry. Representatives of steel and concrete companies mingled with camera fans waiting for a picture in case the column crumbled.

Wright, accompanied by a number of his students, drove from Taliesin, at Spring Green, Wis., to superintend the test. The industrial commission was represented by M. C. Neel, assistant building engineer of the building division, and R. S. King, the building inspector for the commission. H. F. Johnson, jr., president of the wax company, and Mendel Glickman, Milwaukee civil engineer, who checked the figures on the columns for the architect, were also on hand.

Retire for Beer

At 4 p. m., after 18 tons of sand had failed to crack the pillar, workmen and visitors retired to the company recreation building for beer and pretzels, a breathing spell, and a short talk by the architect. After the respite, workers, with the aid of a derrick, continued the task of distributing the weight of sand evenly across the wide top of the steel mesh and concrete post. At 6 p. m. the structure was still standing, and plans were made for continuing the test Friday, adding weight until the column crashes.

The Greeks who had a word for almost everything, had no word to describe the new Wright building column. The column as the Greeks knew it, and even as it is generally known today, either starts thick at the base and tapers near the top or runs the same thickness throughout. Architectural rules which have been evolved from early day column construction also hold that a certain area of base must not carry a column above a certain height.

The column designed for the Racine plant defies so many of these building laws that the commission wanted the test before passing on the construction, Neel explained.

Shaped Like a Flower

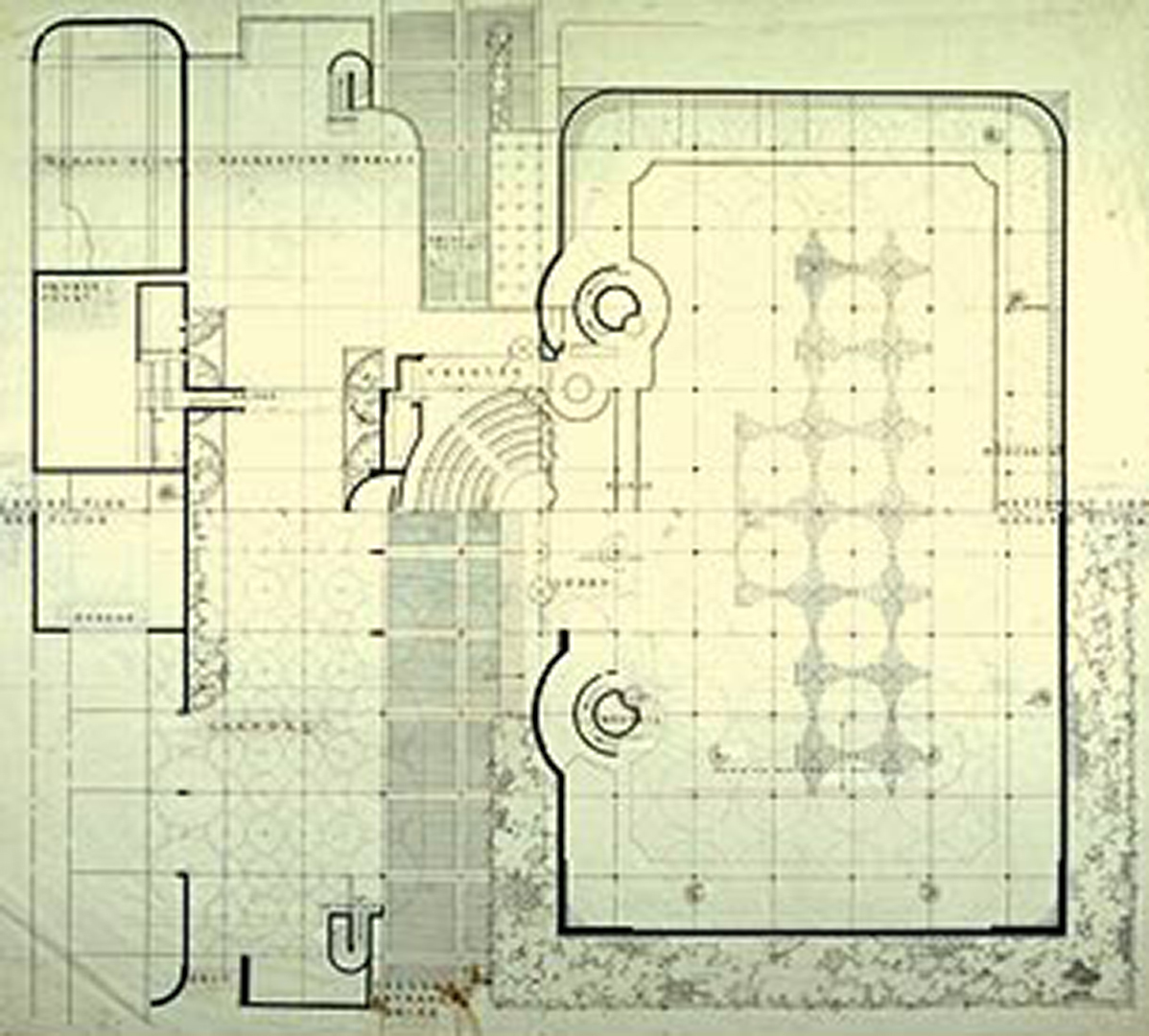

The new column takes the form of a flower, or an ice cream cone. Wright prefers to call it a “flower” column. At the ground, where most columns have their greatest thickness, the Wright column is nine inches in diameter. Instead of tapering, it spreads gradually, like the stem of a flower. At the top of the “stem”, simulating the botanical construction of a flower, there is a perceptible widening of the forms to create the appearance of a cup. Wright calls this the “calyx” from the botanical name for the corresponding part of a flower.

Surmounting the “calyx” is a large concrete “dish”, 8 1/2 feet in diameter, which is called the “petal”. The roof of the building will rest on these concrete “petals”, spaced 20 feet apart throughout the building. Light will be brought into the building through glass skylights which will fill the diamond shaped areas on the roof caused by the rims of the petals.

Breaks Rules on Height

According to builders a nine-inch diameter at the base of a column, can support, a maximum column height of 6 feet 9 inches. The nine-inch diameter of the Wright column carries a height of 21 feet 7 1/2 inches.

Secret of weight carrying ability of the new pillar, according to Wright, lies in its departure from the conventional way of building concrete pillars. Instead of using steel rods to reinforce the concrete, the architect has perfected a steel mesh core.

“Iron rods in concrete represent the bones of a human foot. The steel mesh, however, plays the role of muscles and sinews. Muscles and sinews are stronger than bones. The concrete flows in unison with the steel mesh. It ’marries’ the mesh, so to speak,” Wright explained.

Some of Wright’s students present at the test said that their mentor’s building technique is based entirely on the “marriage” of building materials. He calls it “organic” architecture.

© Milwaukee Journal. Reprinted with permission.

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bgsq%2Bu1KulrGeWp66vt4ylo6ixlGLEs7XGoatoq5Nit7C0zaymp2WYpnqmxNNmoKes